Posted on June 19, 2015

Most of us never even think of poliomyelitis, commonly referred to as polio, much less that it can affect us at all. Our complacency is not surprising as, since the polio vaccine was introduced in 1955, the disease has virtually been wiped out in large parts of the world, including South Africa. This is thanks to a resolution for the worldwide eradication of polio that was adopted by the 41st World Health Assembly that took place in 1988. This resolution marked the launch of the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), which was spearheaded by national governments, the World Health Organisation (WHO), Rotary International, the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and UNICEF. Since the GPEI was launched, the number of polio cases has fallen by more than 99% worldwide.

Polio is a highly infectious disease caused by a virus that mainly affects children under five years of age. The virus invades the nervous system and can cause a type of total paralysis called acute flaccid paralysis (AFP). It is transmitted through contact with the stool of an infected person or through droplets from a sneeze or cough. Initial symptoms include fever, fatigue, headache, vomiting, stiffness in the neck and pain in the limbs. One in 200 polio infections leads to irreversible paralysis, usually in the legs. Among those who become paralysed, 5% to 10% die when the virus affects the muscles that control breathing. There is no cure for polio, but it can be prevented by vaccinating young children against the disease. The polio vaccine, which is administered as part of most countries’ normal vaccination regimen for children, can protect a person against the disease for life. The ‘gold standard’ for monitoring for the presence of polio is based on the surveillance of cases of paralysis or AFP. However, an alternative strategy for detecting poliovirus, particularly in non-endemic countries, is environmental surveillance of polioviruses in sewage. This strategy detects poliovirus importations and functions as an early warning system in the absence of AFP cases.

Despite the success of worldwide vaccination campaigns to date, this devastating disease is still endemic in a small number of countries including Afghanistan, Nigeria, and Pakistan. Although polio cases in faraway countries might not seem like a global concern, it is important to remember that as long as polio is present anywhere in the world, outbreaks are still a risk. Fortunately, according to the most recent statistics, polio cases in Nigeria have dropped by 65%, and the rate of immunisation has risen by 29%. Vaccination efforts in Afghanistan and Pakistan, however, have proved problematic as, in addition to the difficulties involved in reaching villages in remote areas, the efforts of health workers in these countries have been met with violence and resistance from political groups who claim that the vaccination campaigns are part of a Western plot. Sadly, healthcare workers attempting to administer polio vaccinations have been attacked and killed in both of these countries.

Recently, cases of polio have also been reported in Syria. Health experts blame the on-going civil war in the country for the fact that people do not receive vaccinations. Immunisation rates in Syria decreased from 90% in 2010 to only 68% in 2012. Health officials are currently doing everything in their power to get vaccines to children in Syria and other countries in the Middle East. The virus strain causing the Syrian outbreak has also been detected in sewers in Egypt, Israel, the West Bank, and the Gaza Strip.

To assist in the final push for the total eradication of the virus, PATH, an international non-profit organisation and leader in global health innovation, has partnered with the international Polio community to develop specific tools that are needed to aid in the eradication of the disease. Key partners and stakeholders include the University of Pretoria (UP), the University of Washington (UW), the University of Victoria (UVic), the CDC Polio Group, the WHO Global Polio Laboratory Network, Scientific Methods Inc, TwistDx Ltd (a subsidiary of Alere, Inc), and Ustar Biotechnologies (Hangzhou) Ltd.

Two tools have been developed to date. The first is a bag-mediated filtration system (BMFS) where wastewater is passed through a simple filter that binds polio and other enteric viruses. This system is designed to facilitate increased sensitivity to detect poliovirus circulation in a population and will enable scientists to collect volumes of wastewater 10 to 20 times greater than current practice allows. The system also makes provision for the improved capture of the poliovirus in filter cartridges that can be more easily processed by a laboratory. In addition, the use of preservatives on the filter may eliminate or reduce the need for controlling the storage temperature when shipping the filters to a test facility.

|

|

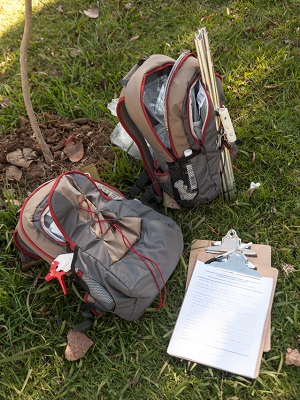

| The bag-mediated filtration system (BMFS) developed by the team | The BMFS wastewater sampling device fits into an easy to carry bag and can be quickly assembled at the test site |

The second tool that has been developed is highly sensitive and simple to use, and facilitates rapid preliminary diagnosis of polio prior to confirmation by a reference laboratory. This tool can also be used to produce enriched and purified viral RNA in a stabilised format that allows for shipping directly to national reference laboratories for genotyping. To develop kits for the rapid preliminary diagnosis in cases of AFP, PATH and Ustar are also developing a reverse transcription cross-priming amplification (RT CPA) assay that requires only a water bath or simple heater to incubate reactions.

Preliminary validation of the BMFS wastewater sampling device is already underway in Kenya with the assistance of the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI). Samples collected using the device are currently being analysed at KEMRI, UP and the CDC. The data obtained will be used to provide insight into the BMFS kit’s performance in the field, but more importantly, the sampling will help in refining the design of the kit, the development of protocols, as well as the streamlining of sample collection and shipping procedures. According to PATH, a critical step towards the eradication of polio will be to ensure commercial access to both the diagnostic and surveillance tools. To this end, they are working with manufacturers and potential commercial partners to negotiate acceptable pricing and supply of all of the main components for both tests.

A five-day event was held at UP in the first week of June 2015 to review the current project data and to give members of the Polio community the opportunity to make critical assessments of the progress of both tools. PATH and the UW also provided training in the use of the tools to staff from country programmes in preparation for introduction and demonstration of the project in the next two years.

PATH and the UW provided training in the use of the BMFS wastewater sampling device to staff from country programmes at the UP's LC de Villiers Sports Campus

The WHO says that once polio is eradicated, the world can celebrate the delivery of a major global public health success that will benefit all people equally, no matter where they live. Most importantly however, the successful eradication of this disease will mean that no child in the world will ever again suffer the terrible effects of lifelong polio-associated paralysis.

Copyright © University of Pretoria 2025. All rights reserved.

Get Social With Us

Download the UP Mobile App