University of Pretoria (UP) astrophysicist Professor Roger Deane was part of the international group of scientists who have captured the first image of a black hole. His group worked to develop simulations of the complex, Earth-sized telescope used to make this historic discovery. These simulations attempt to mimic and better understand the data coming from the real instrument, which is made up of antennas across the globe.

About four years ago, Prof Deane started working with the team on the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), which captured the image that was globally released today (Please see up.ac.za for the official media release). Prof Deane, who grew up in Welkom in the Free State, developed a passion for astronomy from an early age, when he was dazzled by the excellent view of the Milky Way.

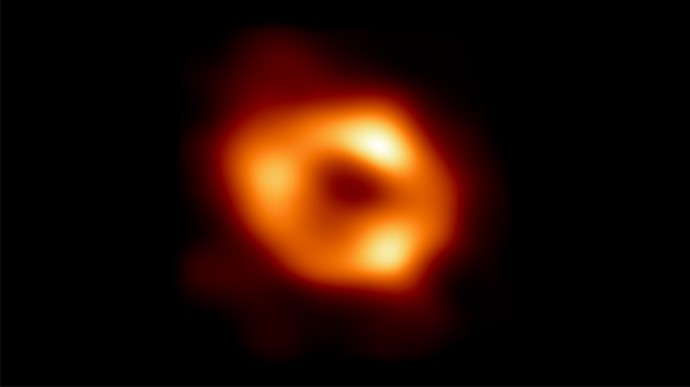

Downplaying his contribution to the capturing of the first image of a black hole, the 36-year-old Associate Professor of Physics said, “I’m still blown away by the image. It hasn’t really worn off yet. I’m just proud and honoured to play my small part in this amazing international team.”

UP Vice-Chancellor and Principal Prof Tawana Kupe congratulated Prof Deane on his contribution to the EHT. "This young scientist is an inspiration to scientists on the African continent. Our staff and students are innovative and creative thinkers who excel in cutting-edge research, and this discovery is a great example of what can be achieved if we work together across borders and disciplines. UP is already at the forefront of world-class research and, as one of the largest knowledge producers in South Africa, we make an impact on issues of critical relevance to Africa and the world. We produce high-quality research that matters,” he said.

According to Prof Deane, as with any major physics experiment, one needs to understand the effects that the instrument itself may have on the data. “In the case of the EHT, we built a simulation package that physically modelled a number of non-desirable effects that prevent one from seeing any sort of black hole shadow feature.”

The EHT observes what radio astronomers consider to be a very short wavelength, about 1 mm, which means the distance between two consecutive peaks of light is 1 mm. “This is about 200 times smaller than the wavelength of light that MeerKAT observes, and presents many challenges to the telescope design, data processing and analysis.”

Prof Deane said, “Just a small amount of water vapour in the atmosphere could completely erase the signature of the black hole shadow. This is why the EHT stations are at very high altitudes in some of the driest places on Earth.” There are a multitude of other aspects to accurately model in an instrument as sensitive and complex as this telescope. “We incorporate as much of this information as we can physically model in software. This accurate simulation of the telescope enables astronomers to better understand the real observations, discriminate between theoretical black hole shadow models, and insights into the characteristics and performance of the telescope itself.” He explained that this also allows scientists to accurately predict the impact of adding new antennas in the global network, as is planned for the African Millimetre Telescope (AMT) project in Namibia.

The first image of a black hole is a significant milestone for the EHT, but much lies ahead as the team works towards testing Einstein’s general theory of relativity. To do so, they will need to continue to improve the images through array expansion in Africa and elsewhere with improved algorithms. Prof Deane says his group is now focused on three things: “Expanding our simulations to model the case where light from the black hole may have preferred orientation – think about how polarised lenses reduce the sun’s glare from the sea – performing detailed simulations on new prospective sites, and exploring a range of probabilistic modelling techniques to extract the properties of the black hole shadow.”

What did it feel like being part of a team of 200 highly talented scientists who have worked on this project?

“It has been a privilege – I have learned a great deal in all spheres. One of the aspects of my job that I love the most is working with astronomers from around the world from a diverse set of backgrounds and perspectives. The dramatic result unveiled today has required a combination of the world’s best engineers, theorists, and observers. I’m thrilled to be a part of that team. It has also been challenging, apart from practical aspects like the geographic and time zone differences.”

At UP, this Y1 National Research Foundation-rated scientist is leading the new Astronomy Research Group which is focused on MeerKAT, the Square Kilometre Array, and the technique of creating virtual Earth-sized telescopes like the EHT and the African Very Long Baseline Interferometry Network.

When he moved to UP in January 2018, there were no other astronomers at the institution. “By July, we should have scaled up to approximately 14. We are hoping to finalise a joint South African Radio Astronomy Observatory-UP South African Research Chair Initiative Chair in radio astronomy by then as well. Over 100 UP students registered for the first year astronomy course in 2019, a dramatic increase, so there is clearly a need to grow the number of faculty positions in astronomy to deal with the teaching and postgraduate student supervision demand.”

The UP Astronomy group’s science-driven approach is in keeping with the realisation that this new era of complex, big-data telescopes requires technical expertise and new algorithmic approaches. A significant part of his UP research group’s work is focused on machine learning with the UP Computational Intelligence Research Group in the Department of Computer Science, and instrumental work in collaboration with UP’s Electrical, Electronic and Computer Engineering Department.

Looking ahead, Prof Deane is very excited about growth in astronomy, saying that, “South Africa has an increasing number of astronomy-related success stories to help spur our youth into science and technology careers. I think our government, through the Department of Science and Technology, has been very strategic in that regard, with payoffs that will be far-reaching and long-lasting.”

Professor Roger Deane on the University of Pretoria’s astronomy programme

When did UP’s astronomy programme start?

UP’s Department of Physics has had astronomy undergraduate courses for many years. The current radio astronomy research group started at the beginning of 2018 with my arrival. UP has among the largest astronomy enrollments in undergraduate courses in South Africa, showing great potential to grow into a large research group.

Approximately how many students do you have?

In July this year, we should have scaled up to approximately 13 (1 faculty, 2 post-docs, 1 PhD, 3 MSc, 6 Hons). We are hoping to finalise a joint South African Radio Astronomy Observatory-UP SARChI Chair in radio astronomy by then as well, which should increase the cohort to at least 20.

Why is big data important, and what is the computational capacity of the MeerKAT and the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT)?

The EHT raw data was 4 petabytes in size. Unlike EHT, which observes one astrophysical object a time, MeerKAT will detect many millions and have archive sizes even larger than an annual EHT campaign. To analyse this data and ensure we enable all the exciting discoveries to come, we have to get in step with the fourth industrial revolution (4IR) and employ artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches. Astronomy is a key contributor to the 4IR, as highlighted by President Cyril Ramaphosa in this year's State of the Nation address. At UP, the Astronomy and Computational Intelligence Research Groups are working closely together to ensure our university plays a leading role in this en route to the Square Kilometre Array. The UP Astronomy group’s science-driven approach is coupled with the realisation that this new era of complex, big-data telescopes requires technical expertise and new algorithmic approaches. A significant part of the UP research group’s work is focused on machine learning with the UP Computational Intelligence Research Group in the Department of Computer Science, and instrumental work in collaboration with UP’s Electrical, Electronic and Computer Engineering Department.

How is UP leading in investing and promoting astronomy as an academic and research discipline?

UP has taken a forward-thinking, strategic approach by investing in the Inter-University Institute for Data Intensive Astronomy (IDIA). It is one of three university partners who are ensuring they will be able to deal with the data processing and analysis demands of MeerKAT and SKA. UP has also taken a strategic decision to invest in the technique of Very Long Baseline Interferometry – the very same approach the EHT uses. This is with a view to taking a leadership role in the African VLBI Network and the second phase of the Square Kilometre Array, ensuring South Africa and Africa are at the forefront of the spectacular science these VLBI arrays will perform.

How does UP’s astronomy programme – and South African astronomy in general – measure up in the global astronomy community?

In the UP Department of Physics, we are building a new astronomy group that is both science-driven and technically savvy. We have demonstrated that in the EHT project, and we are heavily focused on making leading contributions towards MeerKAT, which will eventually extend across the African continent as the SKA. It's important that South Africa benefit scientifically from the astronomy investments that the South African government has made through the Department of Science and Technology. To do so, universities need to play their part in investing in research expertise. UP is in the process of stepping up to that responsibility, with this EHT announcement being a first example of the fruits of that investment.

Stories

Stories

Gallery

Gallery

Video

Video

Infographic

Infographic

Infographic

Infographic

Story

Story

Get Social With Us

Download the UP Mobile App