How do people who cannot speak consult with their doctor and tell them what is wrong?

To answer this, researchers at the University of Pretoria’s (UP) Centre for Augmentative and Alternative Communication (CAAC) in the Faculty of Humanities conducted a study that involved designing a framework to develop health education material for people with complex communication disabilities.

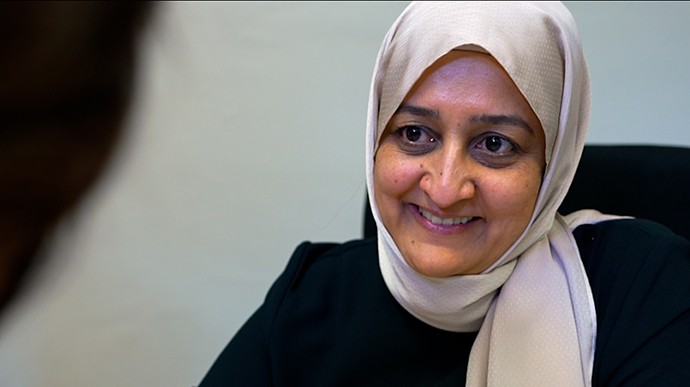

“Those with severe communication disabilities are often marginalised and viewed as people who have nothing to say,” says Director at the CAAC Professor Shakila Dada. “This could not be further from the truth, which is why the centre is committed to ensuring that people have access to various means of communication through augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). We do this in consultation with people who have complex communication needs (CCN) because we believe that nothing should be done for people with disabilities without including them in the process. It is also important to remember that AAC is not about the boards or technologies, but about the people.”

The study was published in the journal Health Expectations and aimed to bring accessibility and justice for people with CCN into sharp focus, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study found that when it came to accessing healthcare, people with disabilities faced difficulties in three distinct areas: interacting with healthcare workers, experiencing feelings of disempowerment and the presentation of healthcare material.

Healthcare providers did not have the skills, time, communication resources or skills to interact patiently with people with CCN. In addition to this, healthcare workers did not have the right attitude; many would speak down to patients with CCN or not give them the opportunity to make health-related decisions for themselves.

People with CCN also had their own internal barriers in terms of their level of empowerment, and their willingness and ability to speak for themselves; their skill at making themselves understood also varied, as well as their access to assistive devices (such as a computer or smartphone) to assist their augmentative and alternative communication needs.

Another barrier was the format in which healthcare information was presented. This included how complex a pamphlet or brochure was to read, the patient’s home language and comprehension levels, how the content was presented and the integrity of the information.

In order to mitigate these challenges, UP’s Centre for Augmentative and Alternative Communication engages the services of a staff member with CCN. Constance Ntuli is a valuable member of the team whose input into this and other projects is critical.

Ntuli lost her voice as a child and got her first assistive communication device in 2009. Her path to a career at the centre began when she attended UP’s Fofa Communication Empowerment Programme; she can now communicate through electronic communication devices.

“My job entails raising awareness about AAC,” she says. “Working at the CAAC has really helped me to improve my self-esteem. I am grateful because it is not easy being disabled and jobless, or clueless about my future. I love helping other people and opening up the world for those who can’t speak by working on projects that greatly help and improve our lives directly.”

As a disability advocate, Ntuli speaks of her experiences as a person with CCN trying to access healthcare. “I really didn’t enjoy going to the hospital, because sometimes I felt judged. As a mother with disabilities, it is sometimes twice as hard. Also, the information is provided so quickly – there are so many terms that I don’t understand and there is no time for me to type my questions on my AAC system or even to respond to questions.”

Ntuli says that the centre’s study is important because it encourages people with disabilities to be independent. “There are some things that I want to discuss with my doctor confidentially,” she says. “If there isn’t privacy and someone else has to speak for me then it means everyone will have to know my medical affairs. Everyone deserves to have privacy and to be treated with the care that they deserve.”

The study was funded by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and has resulted in free-to-use communication boards. Those with CCN can use these to communicate without an electronic device when they go to hospitals and doctors. This offers people a greater sense of dignity and autonomy, especially because COVID-19 restrictions has meant that caregivers often are not allowed to accompany patients. The boards can also be used in other contexts – those with severe speech impediments, low literacy levels or for whom English is not a first language can also make use of them.

Click on the webseries episode in the sidebar to learn more about Prof Shakila Dada’s project and why disability rights and access are human rights.

Click on the next webseries episode in the sidebar to learn more about Constance Ntuli and what drives her.

Prof Shakila Dada and Constance Ntuli

June 26, 2023

Constance Ntuli has been working at the Centre for Augmentative and Alternative Communication at the University of Pretoria (UP) since 2013. She was introduced to the centre in 2009 when she was invited to participate in a youth empowerment programme there. The programme was geared towards youth and young adults who have little or no functional speech, and who rely on assistive technology to communicate in their daily lives.

Since joining the centre, Ntuli – who makes use of augmentative and alternative communication devices (AAC) – has upskilled herself by gaining knowledge and experience in AAC through various projects, research and training programmes. Ntuli is also part of the UNICEF Youth Forum at the centre, and is involved mainly in advocacy work, often delivering talks about her lived experience.

She says her work contributes to the betterment of the world because she is committed to changing people’s mindsets about individuals who have little or no functional speech. “A change in thinking is important – I show people the benefits of assistive technology and how this helps in communicating effectively,” Ntuli says. “I hope that by demonstrating this within my daily life, those who also experience communication difficulties can see that the possibilities are endless.”

Her research matters, she says, because it is about changing mindsets and helping others who, like her, have little or no functional speech. “With assistive technology, and specifically AAC, I can demonstrate how one can live a life of meaning and purpose, and a life of abundance.”

As to whether a specific event or person inspired her, Ntuli names Artscape CEO and disability activist Marlene le Roux. “People like Marlene le Roux inspire me to live a life of passion, purpose and advocacy for others with disabilities,” Ntuli says. “After Marlene was diagnosed, she took the bold and brave decision to not allow her disability to define her.

Ntuli has two other role models: the late Dr Cival Mills and Martin Pistorius. Dr Cival Mills lived with locked-in syndrome and used AAC, and Pistorius is still living with the condition and thriving thanks to AAC. “Both of them authored books and dedicated their lives to advocating for people with disabilities,” Ntuli says. “I hope to follow in their footsteps.”

Her advice to learners and students interested in her field would be to begin with passion about the field of disability. “Be motivated to extend your knowledge by engaging in research. AAC is quite a unique field; you will learn the theoretical side of assistive technology but also engage in the practical aspect by exploring various types of AAC devices.”

In her spare time, Ntuli enjoys going to theme parks. She also loves cooking (and watching cooking shows), fashion and listening to music.

Story

Story

This edition is curated around the concept of One Health, in which the University of Pretoria plays a leading role globally, and is based on our research expertise in the various disciplines across healthcare for people, the environment and animals.

Story

Story

Paediatric neurosurgeon Professor Llewellyn Padayachy, Head of the Department of Neurosurgery at the University of Pretoria’s (UP) Steve Biko Academic Hospital, is redefining how brain-related diseases are diagnosed and treated, especially in low-resource settings. He’s at the forefront of pioneering work in non-invasive techniques to assess and measure raised pressure inside the skull,...

Infographic

Infographic

Africa faces immense challenges in neurosurgery, such as severe underfunding, a lack of training positions and a high burden of disease. There is one neurosurgeon per four million people, far below the WHO’s recommendation of one per 200 000. This shortage, compounded by the lack of a central brain tumour registry and limited access to diagnostics, severely impacts patient outcomes.

Copyright © University of Pretoria 2025. All rights reserved.

Get Social With Us

Download the UP Mobile App